Abstract

Some health care workers, such as nurses, face an increased risk of needlestick injury which occurs when the skin is accidentally pierced by a used needle. Blood-borne diseases that could be transmitted by such an injury include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV).

Data available demonstrate that from 2018 to date, annual needle stick injuries to staff at NMC have reduced considerably. This improvement confirms that staff education, avoiding recapping, reducing injections, quick and accessible sharps disposal and adequate staffing are helping to reduce incidents of needle stick injuries. Ultimately, the adoption of standardized measures will help reduce needlestick injuries and their associated risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

This article offers an overview of best practice interventions taken to address risks faced by staff, patients and their families regarding needle stick injuries. It also highlights the changes achieved and how they can be sustained and internalized at Nyaho Medical Centre (NMC).

Problem

Between 2018 to 2020, approximately 24 needlesticks injuries to staff were recorded. Of this figure, 90% (19) involved nurses. This meant that nurses were highly exposed to bloodborne pathogens such as Hepatitis B (HBV), Hepatitis C (HCV), and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS, through contaminated needlesticks injuries. Several studies highlight the alarming risk rate to nurses and other frontline staff.

Nonetheless, these risk exposures are often considered an integral part of the nurses’ job that must be accepted as an occupational hazard. Another long-term problem includes the risk of seroconversion after a nurse exposes infected blood products to others in the workplace and its effect on the workforce.

According to the study, the following scenarios account for needle stick injuries in NMC:

1. Needle recapping: there was evidence that recapping and other hand manipulations of needles existed. If recapping is necessary (e.g., if performing a procedure in a situation in which sudden patient movement is possible and not preventable), using a singlehanded scoop technique for recapping will be necessary.

2. Lack of any organized training routine in safe injection practices to equip nurses with knowledge on preventive behaviors and risks associated with needle stick injuries.

3. No quick and accessible sharps containers around the bed space for safe disposal. Consequently, nurses had to walk distances to access sharps containers.

Background

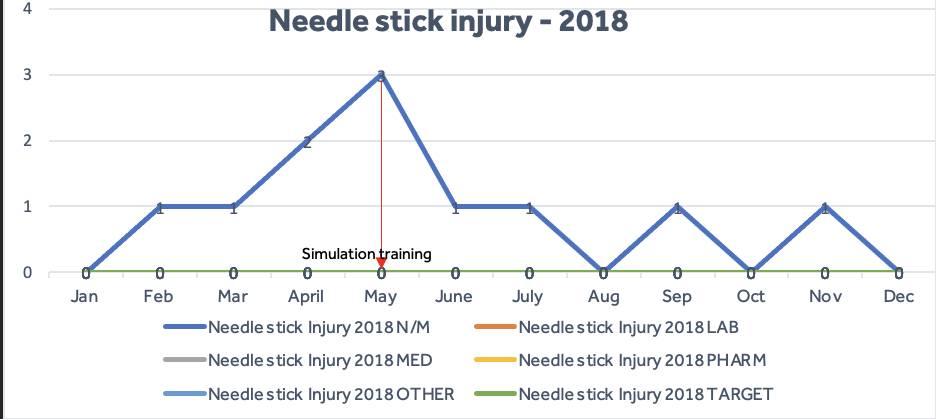

In 2018, eleven (11) injuries were reported (figure 1) with three recorded in May. A major concern for Nyaho was the number of incidents that may have gone unreported. Evidence suggests that unreported needle stick injuries may be as high as 85%. Given the number of nurses and other health care workers affected by needle stick injuries, it became necessary to address the problems to ensure patient and staff safety. This necessity occasioned investigations into needle stick injuries using our patient and staff safety case review processes where the root cause analysis and action hierarchy methodology was applied.

Furthermore, Nyaho Medical Centre needed to create a conducive environment with effective measures to reduce the recapping of needles to avoid injuries and prevent exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Also, we understood that providing routine simulation training for nurses and other healthcare workers about the risk was a good way to go. Likewise, there was the need to provide a quick and accessible ‘point of care’ sharps bin for safe disposal. This particular action sought to eliminate the potential risks posed to workers who transport contaminated needles away from the bedside.

Baseline Data

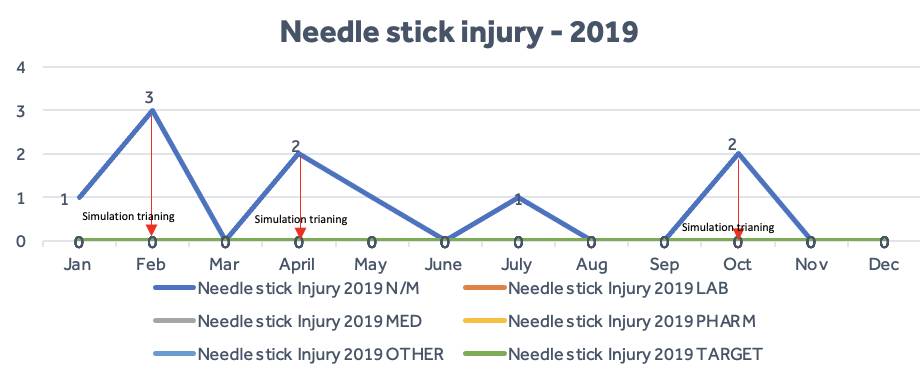

In 2019, ten (10) cases of injuries were recorded (fig 2). During case reviews, it was established that the most probable causes of needlestick injuries were recapping and lack of awareness of preventive behavior. Thus, it became necessary to adopt intervening actions upon recommendations. Interventions such as simulation training were prescribed to create awareness of the risks of needle stick injury. However, these were not sustainable because of work overload. We started collecting data and reported daily the number of staff who knew of a colleague who had sustained an injury or perhaps had been stuck themselves.

This was done to underscore the need to understand fully the risks of exposure to bloodborne pathogens through contaminated needlesticks or sharps. With regards to patient safety, this was looked at on both an immediate and long-term basis. Acutely, there was the simple risk of a sharps-related injury plus the potential exposure to hazardous blood products.

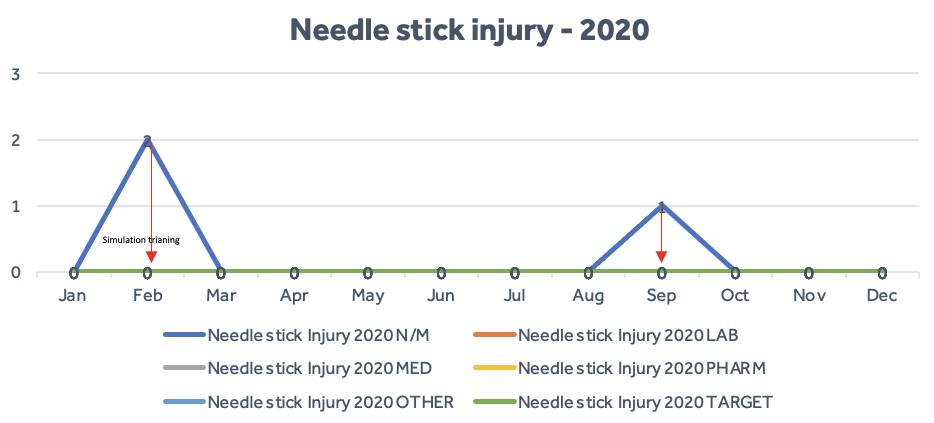

evidence to help Nyaho prioritize the reduction of needle stick injuries. Subsequently, we developed metrics to track and measure incidents of needlestick injuries and safe staffing per each department. These were reported as a key performance indicator (KPI) on a monthly, quarterly, and yearly basis to the CEO, Clinical Governance Committee, and the Board of Directors. These actions culminated in a significant reduction in needlestick injuries in 2020 (three injuries were recorded).

Initially, incidents of needle stick injuries were generally reported from wards and the diagnostics department. With time, following improved awareness creation, many staff of differing roles and disciplines across Nyaho also reported incidents of needle sticks. The reporting process, however, divulged staff’s identifiable details and that was unsafe as staff often became anxious that they may be punished or blamed for reporting the incident.

This reporting process was inimical, as we wanted to ensure that all incidents and near misses of needle stick injuries were reported and reviewed to reveal useful insights for learning. It was in line with Nyaho’s pursuit to establish a safe culture ecosystem including non-punitive, reporting, learning, blame-free and just cultures. With the significant number of injuries recorded in 2018 and 2019, redefining safety culture and implementing interventions became a necessity.

The reporting and case review processes helped to establish the scale of the problem and highlighted differences in practice regarding the handling of needles and the safety of staff within Nyaho Medical Centre. Also, knowledge and awareness of preventable behaviors and risks associated with needle stick injuries were lacking.

Likewise, it was evident that needle recapping and lack of knowledge and awareness of single-handed scoop technique of needles existed (appendix 1). On several occasions, we found that inadequate safe staffing, which results in a high patient-to-staff ratio led to nurses working more hours than established standards. Besides, they could not continue to provide simulation training in any sustainable way.

Design – Shifting the bevel

Following assessments of the learning and development needs of staff, we designed simulation training for staff to address the lack of knowledge and awareness of preventative behavior and the risk associated with needle stick injuries. The simulation training was routinized for both existing and newly recruited nurses about safe injection practices to create the knowledge and awareness that every percutaneous needlestick and sharps injury carries a risk of infection from bloodborne pathogens.

To address the staffing gap phenomenon, we undertook a review, which demonstrated the need to establish a safer staffing level. This resulted in the application of policy development and SOP (best practice) for safe staffing thereby allocating an adequate number of nurses per shift. Likewise, skill mix teams were established to ensure that there was a mix of competent and novice staff to deliver care at every shift level. The practice was extended to other departments across Nyaho whereby heads of departments were reporting on staff-to-patient ratios and skill mix. This resulted in the development of a metric to measure performance at the department level and reported as part of the integrated performance of Nyaho. Moreover, the lack of access to sharps containers was addressed by procuring more containers and placing them in proximity to patients’ bedsides.

Additionally, certain work practice controls were initiated, which included no re-capping, placing sharps containers at eye level and arms’ reach, checking sharps containers on shifts and emptying them before they are full, and establishing the means for safe handling and disposing of sharps devices before beginning a procedure.

It is important to note that these measures are not a universal solution. They are rather part of a holistic approach to reducing exposure of staff to needle stick injuries with associate risk of bloodborne pathogens and should be used in conjunction with already established measures. The section below highlights some of the most effective sustainable control measures in reducing needlestick injuries.

These interventions have led to several changes in preventative behaviors including educational and training programs and activities, establishing a self-report system and culture of modeling behavior of competent and experienced nurses, adherence to standard operating procedures (SOP) that promote zero NSIs and designating safe areas for safe needle handling procedures. Both education and pieces of training raised nurses’ awareness and knowledge regarding best practices, NSI prevention, and management.

Studies confirm that interventions such as following standard operating procedures (SOP), reflections, coaching and mentorship, and self-reporting affect the NSI rate. This led to the redesigning of the supervision and coaching program to provide accurate knowledge to drive preventative behaviors by encouraging adherence to the SOP by new joiners and existing nurses.

A study reports that good behaviors come from sound awareness and a strong correlation between knowledge and NSI prevention. The outcome of the redesigned supervision and coaching demonstrate significant competence in the new joiners underpinned by their understanding of precautions and awareness of the standards. In short, the interventions played an important role in improving nurses’ competence leading to acceptable behaviors that promote safe practice.

Additionally, we have institutionalized an overarching functional orientation program led by experienced senior nurses (mentors/coaches) in the proper use of safety equipment for all standard procedures, proper disposal of used needles and sharps. As role models for the new joiners, mentors or coaches ensure that new joiners adopt good preventive behaviors.

Effective communication and awareness of safety cultures such as non-punitive reaction and blame-free disposition along with adequate supervision have also prevented underreported incidents. Furthermore, it has helped new joiners to feel safer and confident to perform certain procedures without injuries.

Control measures – The next steps

The most effective ways to sustain the impact of the preventable behaviours are laid out as part of control measures to reducing needle stick injury in Nyaho Medical Centre. They include:

i. Undertaking continuous education and training activities that emphasize self-reporting culture of safety, modelling behaviour through mentorship, adherence to standard operating procedures (SOP) to promote zero NSIs.

ii. Introduction of needle stick injury ambassadors, the functional orientation of new staff and allocation of resources (safe staffing) demonstrating a commitment to nurses’ safety, infection control committee with a focus on needlestick prevention, a post-exposure plan, and consistent training to promote a standard for preventing needlestick injuries.

iii. Continued campaign (posters) against a two-handed technique of recapping. If recapping is necessary, nurses must use a one-handed scoop technique.

iv. Collection of used sharps at the point of use in a puncture and leakproof container which can be sealed shut when three-quarters full.

v. Maintain an adequate supply of puncture and leak-proof sharps containers to enable providers to perform procedures conveniently.

These control measures have been designed to assist NMC to reach international standards that is International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Joint Commission International (JCI) of quality and patient safety. It enabled us to conduct assessments to identify how well we were meeting defined standards in two key areas:

• Quality Measurement and Improvement

• Patient Safety

The assessment was not, in itself, intended for use as an accreditation tool. Nonetheless, it is likely to be a useful tool for NMC as we are actively considering international accreditation.

Implications for policy

There needs to be a policy revamp to recognize advances in technology to needlestick safety and prevention. This may require the use of safer needle devices to prevent needlestick injuries.

Essential occupational health and safety measures include:

• Proper training of workers

• Provision of equipment

• Standardized safer staffing

The implementation and enforcement through a legislative or regulatory policy of control measures would enhance and sustain the prevention of needlestick injuries. Recognition of the risks of exposure to bloodborne pathogens by nurses and by regulatory authorities is crucial. While the primary prevention measures have reduced incidents, it is not enough to warrant staff safety. There is, therefore, the need for concerted programs and policies to protect nurses and other frontline workers.

Conclusion

This article aimed to report measures taken to address risks faced by staff, patients, and their families regarding needlestick injuries in Nyaho Medical Centre. This article has reported a significant problem with the incidence of needle stick injuries to staff, the needed interventions, and outcomes (preventative behaviors) established to ensure safety. It also revealed disparity across Nyaho since some departments were reporting and tracking needlestick injuries while others did not. With this information and the advent of (IFC) and JCI regarding international standards for safer needle practices, we would gain support around sustainable control measures. The net results of these measures suggest the need for hospitals to adapt controls to maintain better, safer, and more advanced safety needle practices. Hopefully, it will suggest the same to other healthcare facilities in Ghana.